Principles of effective health comms and how the UK Govt’s Covid-19 response compares

The WHO Strategic Communications Framework is a useful document that is based around outlining the key principles for effective health communications. Its purpose is:

To provide information, advice, and guidance to decision-makers (key audiences) to prompt action that will protect the health of individuals, families, communities and nations.

The publication even has sections on how to encourage action during a health emergency, citing examples such as Ebola and Zika Virus and so provides a perfect lens through which to analyse the Government’s communications strategy during Covid-19.

I’m going to use this model to broadly assess the Government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic (although there is only space to cover so much in here!). The principles of the framework could be used by any health communications professional looking to elicit change in the behaviour of its target audience, so it’s worth adding to your toolbox.

The 6 principles

Accessible

This principle is all about ensuring that the channels of communication are accessible to the target audience. The document identifies a range of options including mass media, owned websites and social media channels. It also suggests that the selected channel may differ depending on the action that you want the audience to take, for example:

mass media is the best way to generate awareness

social media, where people can see examples of others following the message (social proof), is the most effective for behaviour change.

In the case of an emergency, the document suggests creating emergency specific web pages.

How the Government fared

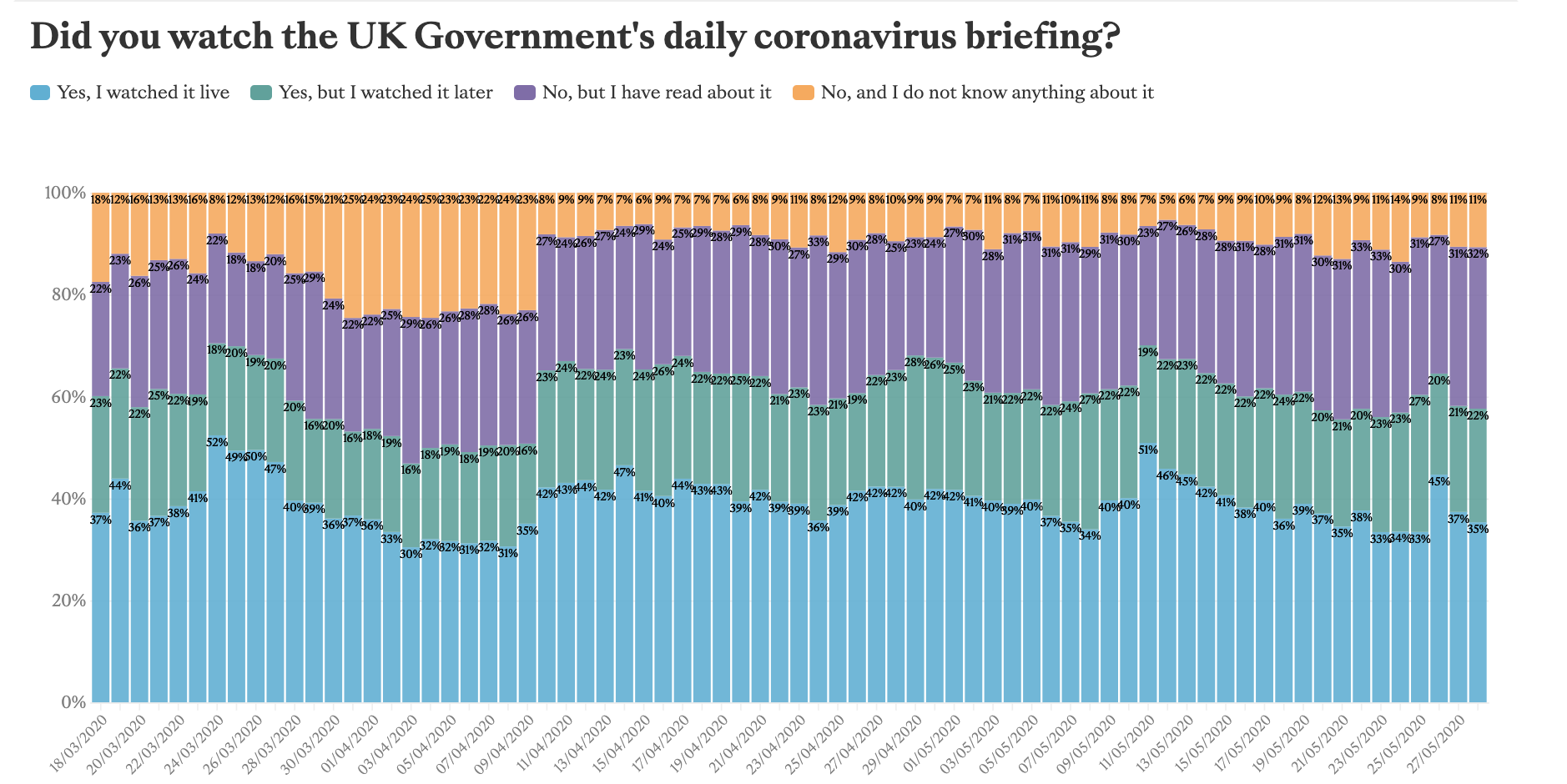

In the early stages of the pandemic the Government was criticised for releasing vital public health information to specific outlets rather than being fully transparent, and this intensified when the Telegraph published some of this content behind a paywall. The move to the daily briefings was hugely important in terms of accessibility and the below graph from Savanta shows that they’ve consistently been watched by 60% of the public, which is extremely high engagement. Social media appears to have been effective early on in increasing the sense of solidarity (and peer pressure) to follow the rules, though it has also amplified division and resentment when it has been felt that some groups are following the rules less stringently than others. Gaps in accessibility have remained, particularly for disadvantaged groups, for example British Sign Language issued legal proceedings against the Government for discrimination over their failure to provide a sign language interpreter at the daily briefings, with the Government finally introducing this change on 21st May.

2. Actionable

The Communications Continuum Model

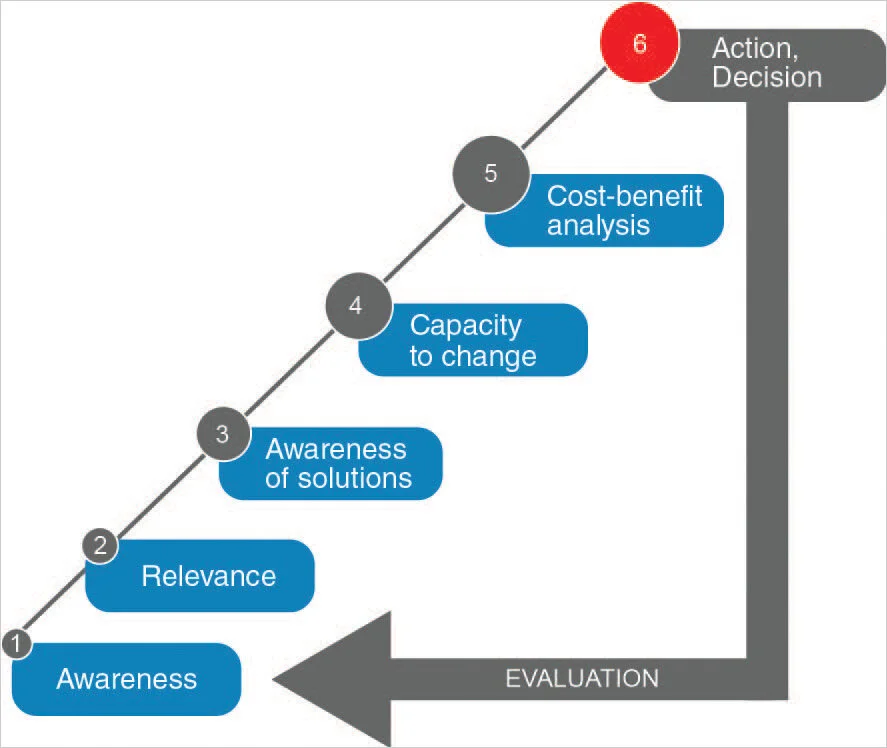

This principle is designed to ensure that communicators understand their target audience’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in order to create messages that resonate with them and achieve the desired outcome. Some of the key considerations are ensuring that the target audience understands the situation, the health risks and the recommended behaviours; that they see the issue as relevant to them and feel personally engaged with it; that they can see the benefits of adopting the behaviour change as well as the consequences of failing to do so and that the communicator has an understanding of the social norms that exist that could get in the way of people adopting the desired behaviour change. The WHO references the communications continuum model as a way to help encourage action.

How the Government has fared

There is no doubt that the Government was slow to act in response to the rising urgency of Covid-19 and we’re sadly still seeing the impact of that now. Once it did so though, the ‘Stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives’ message was a fantastic example of public health messaging. The instruction was clear and simple, the benefit tangible to its audience and it created a social contract that was widely followed. PR Week described how it led to “a remarkable act of civil obedience that few could have predicted before the middle of March” and surveys showed it achieved 92% prompted awareness.

Its successor, ‘Stay alert, control the virus, save lives’ has not fared so well, having been roundly criticised for lacking clarity and being too open to interpretation. If we apply this second message to to the communications continuum above, the lack of clarity in ‘Stay alert…’ results in it feeling irrelevant to the individual, who is also left unsure of how they would follow it and what the benefit would be of doing so. Social media analysis of the message revealed that it had a negative sentiment of -14 and the enormous collection of memes doing the rounds on Twitter show that it wasn’t taken the slightest bit seriously.

3.Credible and trusted

This principle describes how the more the target audience trusts the communicator, the more likely they are to believe and act on the information provided. To reinforce trust, the communicator must demonstrate competence, openness and honesty, dependability and commitment and care. It must show that it has expertise, is committed to its mission of protecting people, is transparent in its work and does what it says it will do.

How has the Government fared

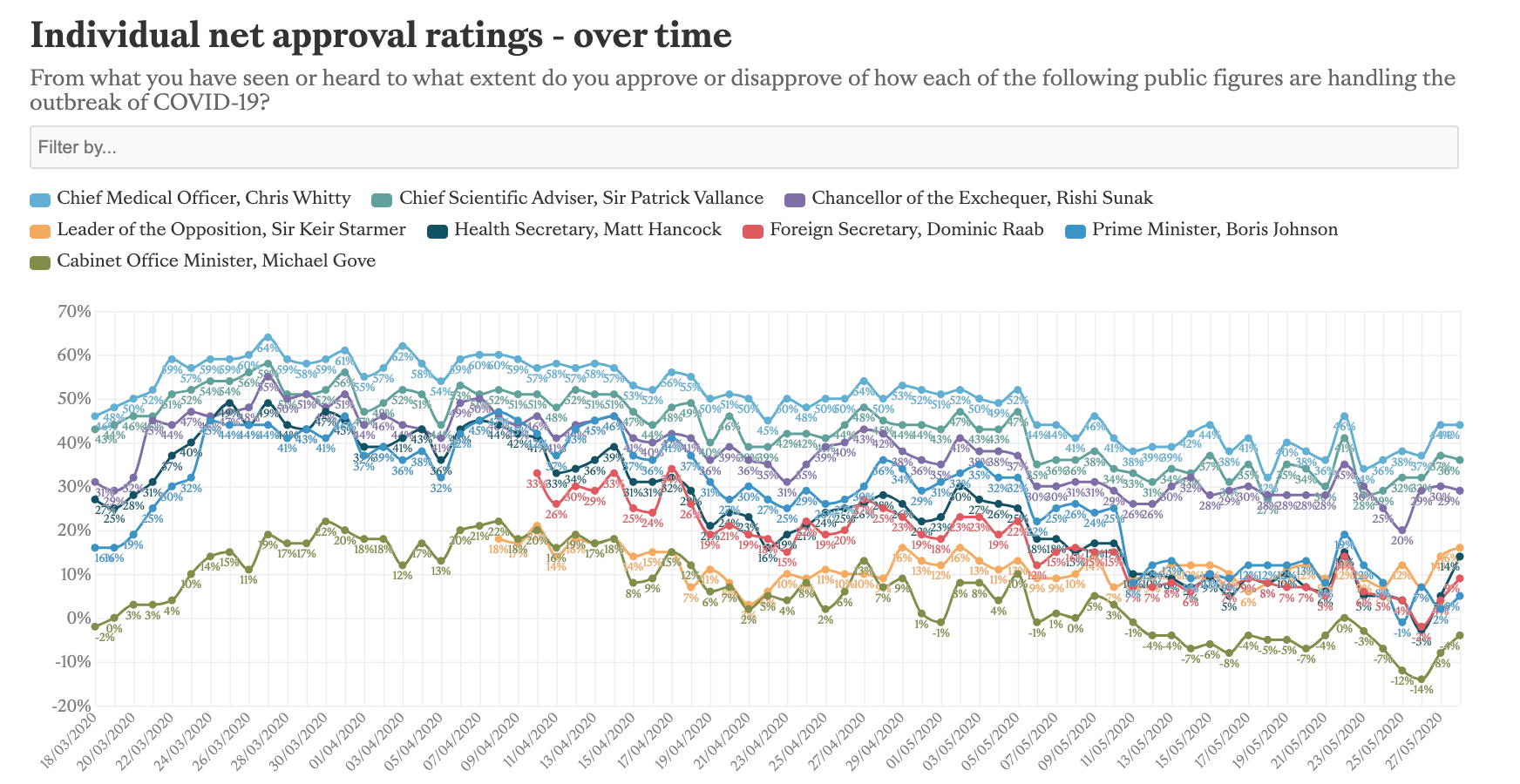

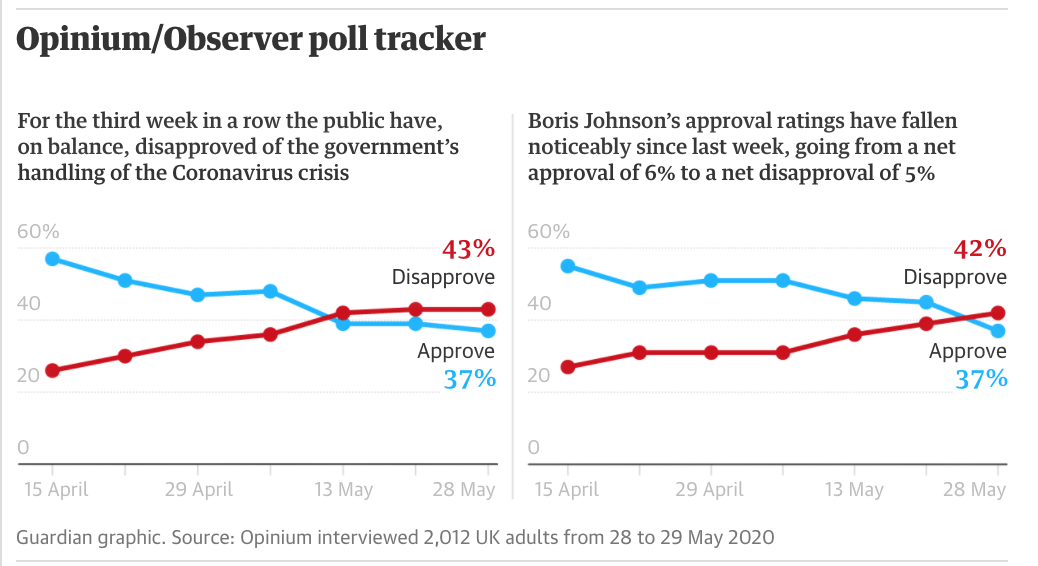

The first daily briefing was on 16th March and, in the two weeks that followed, the Government announced the furlough scheme (20th March) and the UK lockdown (23rd March). These measures significantly increased the trust in and credibility of the Government and the below graph illustrates how net approval ratings of the individuals involved saw a rise around this time.

However, the controversy around Dominic Cummings’ breaking of the lockdown rules (the press conference eventually took place on 25th May after several days of growing speculation), led to a drop in the approval rating of all key Government figures - aside from CMO Chris Whitty and CSA Sir Patrick Vallance, who are by definition not political.

Following this, a blog post by the London School of Economics warned that the Government’s handling of Dominic Cummings’ breaking of the lockdown ‘risks undermining the message of social solidarity’ and could reduce the number of people complying with the lockdown, while a letter signed by 26 senior UK academics and health administrators said that, for compliance, the public must “trust and respect both the messages and the messengers who are advocating action.”

Furthermore, over the weekend several scientists that are part of the SAGE advisory committee suggested that lockdown measures are being lifted too early and that the Government is no longer following the science. The most damning of these was a comment by Professor Rob West, who said:

“This should not be treated as a political crisis but as a health crisis: if you treat it as a political crisis it’s all about managing your reputation; if you treat it as a health crisis it’s about saving lives.”

The discussion in mainstream media has now turned to whether the motivation for the lockdown being eased and for the release of ‘good news stories’ such as the return of the Premier League is to deflect attention away from the Cummings saga. Whether right or not (and we would all hope not), this kind of speculation further undermines the Government’s credibility and reduces people’s belief that the Government is acting in its best interests, and that is likely to impact on behaviour.

4. Relevant

To be relevant, the WHO guidance says that communications must help audiences see that the health information, advice or guidance is applicable to them, their families, or others they care about. It is important to listen to the target audience and public opinion and to tailor messages to motivate the audience, for example by communicating the impact on them or others they care about.

How the Government fared

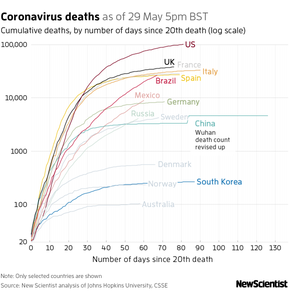

In the early stages of the outbreak, the condition was likened to flu. The perceived low risk to people under the age of 70 - coupled with the delayed lockdown - could also have led to a false sense of security and caused many to believe that the risk was not relevant to them. This could be one factor behind the UK’s aggressive early upward trajectory, which set us on the path for becoming the worst-affected country in Europe.

As understanding of the infection increased there was a noticeable shift in emphasis towards the importance of taking steps to protect those most at-risk, rather than ourselves. The London School of Economics suggests that this created:

“a common fate, a shared identity and the idea of acting for the common or social good, centred around national sentiment towards the NHS’.

The element of social proof that we’re in this together is an important part of communicating relevance to the public. In order to maintain relevance for its messaging, the Government is now under pressure to respond to the one million petition signatories that have called for Dominic Cummings to be sacked and the 100 Conservative MPs that have criticised his behaviour. In fact, police officers have already reported that those breaking lockdown rules are using Cummings as an excuse for their own behaviour and, over the weekend, there were reports of large gatherings at beaches, despite warnings to avoid crowds.

5. Timely

The framework suggests that advice and guidance must be made available in a timely way, so that audiences have the information they need when they need it to make appropriate health decisions. It is stated that there should be a focus on channels that will engage priority audiences quickly, important information should be communicated as it arises and messages should be sequenced to build up the conversation over time.

How the Government has fared

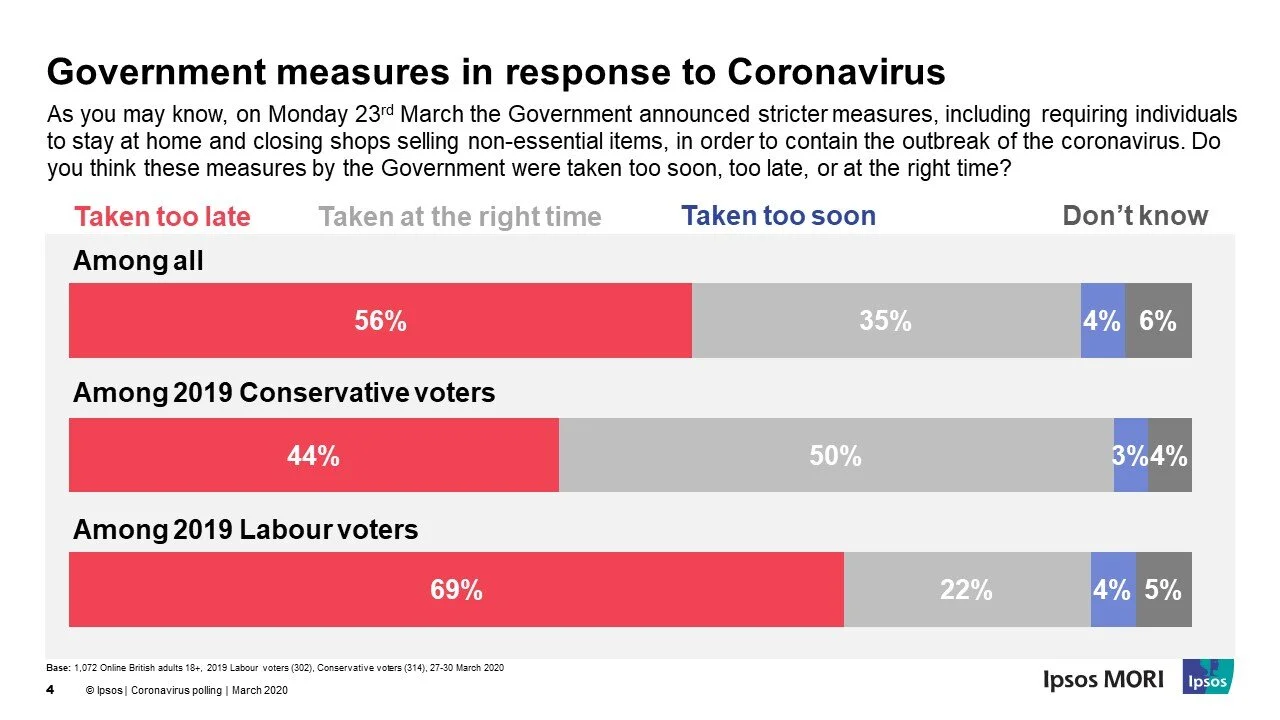

More than half of Britons believe that the Government was too slow to lockdown and to introduce social distancing measures. This suggests that people don’t feel they were given the correct information and support at the time they needed it. The initial reluctance to provide daily briefings on television also meant that information was slow to reach its audience in the early stages.

The failure in timing is thought to be continuing now. This weekend scientists that sit on the Government advisory committee SAGE have warned that the UK is coming out of lockdown too early and that it is ‘no longer following the science’. Landing ahead of a sunny weekend, this messaging led to a big reduction in social distancing (see below photo) at a time when the R rate is still close to one, meaning there is an increased chance of a second spike.

People make their way down to the sea at Durdle Door, Dorset

6. Understandable

The framework suggests that information needs to be easy to understand if action is to be taken. The level of this information will depend on the nature of the audience, how familiar they are with the topic and what the important message you need them to take away. Simple language should be used ahead of technical terms, long and complicated information should be broken down into simple points and visual cues should be used where appropriate.

How the Government has fared

Although there have been some successes (the stay at home message in particular) and the expert advice and visual graphs used by the CMO and CSA have kept the public feeling informed, polls show that there has also been widespread confusion. Some 36% said they didn’t understand rules about whether they should return to work or wear a mask and only 28% trusted the Government to give a clear picture about what everybody needs to be doing or not doing, while businesses such as Barclays have claimed that confusion around the Government’s guidance has prevented the economy from bouncing back effectively as lockdown measures ease. It is possible that with constantly shifting advice and many tiers of messaging to cater for specific groups, such as the elderly or employers, some of the central and most important messages are being lost. And that must be a big cause for concern.

Summary

There is no doubt that the Government has had a hugely complex communications job in this challenging time, the like of which we haven’t seen before.

It is far easier to judge in hindsight and without the day-to-day pressures that are likely to be impacting decisions at times. However, judging the performance against the WHO Framework shows that there have been mistakes.

The slow start left the UK on the back foot and, while the initial clear messages led to exceptional public adherence and a real in-it-together attitude that boosted the Government’s popularity, recent weeks have seen a series of missteps. The ‘stay alert’ message landed badly and trust has been eroded by the decision to stand by Dominic Cummings despite his lockdown breach, while the decision to ease lockdown measures against the advice of the scientific community - after a campaign in which the Government has continually pointed out that it is following the science in its response - has further undermined its own authority at a time when it is needed now more than ever.

If we are to take control of the spread of the virus, changes will be needed to Government communications over the coming weeks. Messages will need to be clearer and informed by the science in both content and timing and leading Government officials will have to take significant steps to show their humanity and prove that we really are all in this together, if they are to rebuild trust in both the messages and the messengers.